by Gene Maddox

My third-grade buddy and I walked gingerly toward Appalachia, Virginia’s new band director. The 1953 Spring Concert was commencing in minutes. First up would be a brief concert by our Junior Band.

My third-grade buddy and I walked gingerly toward Appalachia, Virginia’s new band director. The 1953 Spring Concert was commencing in minutes. First up would be a brief concert by our Junior Band.

I tugged on the director’s pants leg. “Mr. Flanary,” I said, “me and Cliff want to play a duet at the concert.” At that point in our training, Cliff and I were only shakily aware as to which ends of my trumpet and his clarinet were supposed to produce the sound.

“Why, um, yes,” he said, “you may do that.” Cliff and I looked at each other with mild surprise. We’d asked the elementary music teacher to let us sing a duet at the choral recital earlier that year. Clearly aghast, she’d delivered a diplomatic—but firm—“No way!”

The concert audience, fortunately, focused on the cuteness factor as Cliff and I performed, rather than the musicality. And I believe that night to have been the first time a particular thought arose in my young noggin—that there just might be something very special about this band director.

That thought took root and grew during my nearly ten years with “Frantic Flanary and his Frustrated Forty,” followed by the “Tricky Fifty,” and then, of course, the “Tricky Sixty.” My perception of Mr. Flanary’s uniqueness has continued to grow, and to grow substantially, in the decades since my graduation.

The majority of Tricky Sixty alumni, I believe, have experienced these same thoughts. If I were to make a list of the people who have most inspired and influenced my life, the name of Joe Flanary would be very close to the top.

Others have written of Mr. Flanary’s ability to craft stunningly memorable halftime shows and festival performances. And of his persistence in leading, nudging, and pushing us toward musical excellence during the concert season. And of his leadership of small dance bands and groups. And of his instilling in virtually all who served in his bands a deep and life-long appreciation of music.

But Mr. Flanary’s creativity and energy weren’t confined to the world of music. I was fortunate to have been included in two chapters of his life outside that world.

The Entrepreneur

During my junior year, Mr. Flanary decided to open a printing business in his seemingly-quite-sparse spare time. He invited me to join him, as a part-time employee.

This being Mr. Flanary, a typical print shop setup simply wouldn’t do. Other area printers were tied to the traditional processes of printing—metal typesetting machines, along with metal screens for printing photos. It all seemed to have emerged, little changed, from the Gutenberg era.

Mr. Flanary, however, opted for a then-new printing process called “photo-offset lithography.” The printing was photographically-based, with nary a slug of metal type to be found. The result was printed material of a substantially higher visual quality. And the cost was considerably more efficient for the shop’s customers.

Flanary’s Graphic Arts was located on the second floor of the Johnson’s Jewelers building. I loved the work. Mr. Flanary’s son, Ron, helped us from time to time. A forest ranger, Carl Collins, handled the press runs during his off-days.

Our shop produced printed materials for businesses, churches, and other organizations. We even did printing work for the famed Sebring International Raceway in Florida. We teamed with a Big Stone Gap businessman to produce TV Guide-like weekly television listings.

Few people would have thought of our town as a site for the printing and publishing of books. But, indeed, it was for a time. A local barber, L. B. Young, advertised for amateur poets across the country to send their poetry to him. Many did. And they’d pre-order books containing their poems, to be given to their family members, friends, and local libraries. L.B. would pass the poems on to us for printing. He did well with his enterprise, and the printed books were of good quality. Some of the poems, each of which I had to retype on one of our machines, weren’t all that bad either.

When I worked at the corporate headquarters of Pet Dairy Division years later, we found that many of our 60-plus plants and distribution centers often paid high prices for their printed forms. The printing was sometimes of dubious quality and consistency. I set up an in-house photo-offset print shop at the headquarters, hired an experienced printer, and consolidated all our printing work there. It saved Pet Dairy many thousands of dollars over the years. “Thanks, Mr. Flanary,” I said to myself.

The Publisher

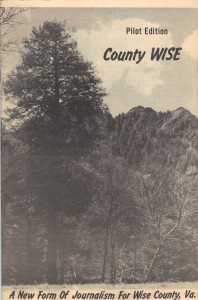

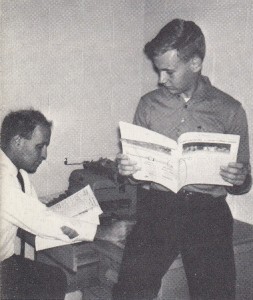

Mr. Flanary’s next enterprise was an even greater surprise than his printing business. He founded a magazine targeted toward Wise County, naming it “County WISE,” and serving as its publisher.

He asked me to work as a writer and reporter, but many others also contributed. AHS teacher Bill Locke wrote about a new manufacturing business. Carol Collier, who’d later pen several novels, wrote of trends in ladies’ fashions and home decor. Cid Davidson, a Clinch Valley College student who’d also write several books in future years, provided a work of fiction. I wrote about the town of Derby, and the efforts of its citizens to revive the local coal industry.

CVC professors Lester Wilson and Edward Henson contributed articles. Local cartoonist Cairo Sturgill provided humor, as did writer Winston Jones. Ron Flanary, who’d later become a nationally-recognized photographer and writer of train-related topics, described the days of steam locomotives in Wise County.

Ron also contributed to County WISE’s coverage of famed Civil War locomotive The General, as it made stops in Wise County during August 1962. Local photographers Don King and Morris Burchette shared examples of their award-winning pictures. The magazine’s circulation increased with each issue, as, seemingly, did the enthusiasm of its readership.

Mr. Flanary had told me I had a degree of writing skill, but that I was doing a poor job of utilizing it. He encouraged me to improve, and I did try. I’m not sure I ever came close to his standards, but I wrote a technology column in a regional business publication for a number of years. I had several articles published in computer and business magazines, and even one in a dog magazine. The latter, to my astonishment, won a national writing award. “Thanks, Mr. Flanary,” I said to myself.

The Leader

The most troubling incident of my years in the band occurred when I was a sub-freshman. The first-chair trumpets at that time were Kenneth Collier, Peggy Jo Blevins, and me. Peggy Jo and I were reasonably capable players, I suppose, especially considering our ages. Kenneth, however, was an upperclassman whose trumpet playing was in a league of its own. He could, at times, almost make an entire football stadium ring.

The most troubling incident of my years in the band occurred when I was a sub-freshman. The first-chair trumpets at that time were Kenneth Collier, Peggy Jo Blevins, and me. Peggy Jo and I were reasonably capable players, I suppose, especially considering our ages. Kenneth, however, was an upperclassman whose trumpet playing was in a league of its own. He could, at times, almost make an entire football stadium ring.

But then the unthinkable happened, only days before the Bristol Band Festival. Kenneth broke his leg, and would be unable to go with us. Peggy Jo was apprehensive. I put on a brave front, but my confidence level was no higher than hers.

Mr. Flanary called Peggy Jo and me into his office for a talk. He was calm, soothing, and matter-of-fact. “It’s in your hands,” he said. “Kenneth won’t be there, and that’s the reality. You two have to ‘pick up the slack.’ I have no doubt that you can do it.”

And we did pick up the slack. Not just Peggy Jo and me, but all the trumpet players, and the players of the other instruments as well. As I recall, we even did a bit better at the festival than merely okay. We used Kenneth’s absence as an opportunity to grow. And later, when we were back at full numerical strength, we found that we’d become a stronger band than ever.

Several years ago, I served a term as the congregational president of our church. As I began my term, we’d had several families to draw away, due to a denominational controversy. Others had pulled back in their giving, because of the uncertainties of the economy.

In my monthly report to the congregation, I shared the story of Kenneth, Peggy Jo, and me. I told of what Mr. Flanary had said to us that day in his office, about picking up the slack.

“The reality is that there are bills to be paid, in order that our work as disciples can move forward,” I said. “Those of us who remain in our congregational family are responsible for ‘picking up the slack.’ And when we’re back at full numerical strength—as the pastor’s list of prospective members indicates will come to pass—then we will find ourselves to be a stronger band of disciples than ever before.”

Just as with the Tricky Sixty at the Bristol Festival, our congregation did indeed pick up the slack. And, as the band had done all those years ago, we became stronger and more cohesive than ever.

“Thanks, Mr. Flanary,” I said to myself. “Thank you so very much, sir.”